Ever since I was born and could see,

Everywhere I looked, I saw dance.

In the clouds as the wind blew them across the sky,

In the ripples on a pond,

Even in the sea of ants marching up and down their hills.

Dance was all around me. Dance was me.

As a young girl, Melanie Kirkwood Marshall ’15 wanted to dance. If Sassy could, why couldn’t she?

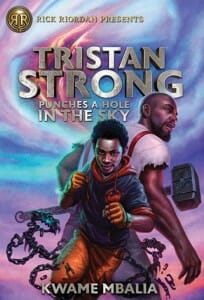

Over and over again, she read that opening passage of Debbie Allen’s children’s book Dancing in the Wings. She pored over Kadir Nelson’s sparkling illustrations of Sassy, a young black girl who, her classmates tease, is too tall to dance. Encouraged by her family, Sassy dances anyway. And after winning a big audition, she concludes: “Mama was right — being tall wasn’t so bad after all.”

Kirkwood Marshall, now a doctoral student of language and literacy education at the University of Illinois, recently looked through her old copy of Dancing in the Wings and discovered a note from her mother scribbled on the endpapers: Always love yourself.

Kirkwood Marshall, now a doctoral student of language and literacy education at the University of Illinois, recently looked through her old copy of Dancing in the Wings and discovered a note from her mother scribbled on the endpapers: Always love yourself.

“I didn’t know it at the time — no kid would be thinking, ‘Oh, my mom got this because it validates my appearance’ — but I leaned on that book heavily for understanding who I was and what I wanted to do,” says Kirkwood Marshall, who is African American.

Such is the importance of multicultural children’s literature. Scholar Rudine Sims Bishop famously coined the phrase “mirrors and windows” — meaning that a good book can serve as a window to an unfamiliar world, a mirror for self-affirmation, or, ideally, both.

But for all the potential, mirrors for children of color have been scarce. Dancing in the Wings was one of some 5,000 children’s books published in the U.S. in 2000. Only 147 of them — less than 3 percent — featured black characters. Only 151 books combined featured Asian, Latino/Latina, or indigenous characters.

Today, more than half of K–12 public school students are children of color, yet less than 15 percent of children’s books over the past two decades have contained multicultural characters or story lines. In 2018, roughly 10 percent of all children’s books featured black characters, 7 percent featured Asian characters, 5 percent featured Latino/Latina characters, and 1 percent featured indigenous characters.

These troubling numbers come from the UW Cooperative Children’s Book Center, or CCBC, which has become the authoritative source nationally for tracking diversity in children’s and young adult literature. Since 1985, the center’s librarians have indexed every new book, providing data for a long-overdue reevaluation of the publishing industry and promoting a more accurate reflection of a diverse world.

Along the way, their efforts have collided with century-old barriers in children’s literature. And although there’s reason for optimism, their work is far from over.

“I Feel Guilty When I’m Not Reading”

Despite its name, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center is for adults.

“We always say, ‘We’re a collection of books for children and teens for adults who work with children and teens’,” says Kathleen T. Horning ’80, MA’82, director of the CCBC, which is part of the UW School of Education and supported by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction.

The center opened in 1963 with joint funding from the state and the university — hence cooperative — as a resource for Wisconsin’s librarians and teachers to assess new books and donate their old ones. Thanks to major investments in education by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, public school libraries suddenly had money and sought guidance on how best to spend it.

The UW campus didn’t have space for an unproven library, so the CCBC opened on the fourth floor of the state capitol building under the massive dome. It expanded and moved to the new Helen C. White Hall in 1971, and later to its current home in the Teacher Education Building.

Now with an established reputation, the CCBC receives nearly every children’s book from American (and some Canadian) publishers — as many as 3,500 per year. Its four librarians — Horning, Megan Schliesman MA’92, Merri V. Lindgren ’88, MA’89, and Madeline Tyner MA’17 — each read and evaluate upwards of 1,000 volumes per year. “You do that at home,” says Schliesman, laughing. “If you didn’t have a passion for it, you would hate this job. I feel guilty when I’m not reading.”

The CCBC highlights the best 250 books of the bunch in its annual publication, Choices, which emphasizes diverse works. Outreach remains central to its mission, with the librarians frequently traveling the state to speak to teachers and librarians. The center also provides information to Wisconsin schools and libraries responding to book challenges from community members.

The CCBC’s library contains a current collection of all new publications, a permanent collection of recommended books, and a historical collection of previously acclaimed works. The vast inventory serves as a treasure trove for UW students and faculty conducting research on children’s literature.

According to Horning, no other children’s book center offers such a range of services — from reviewing books and gathering data to shelving every publication and traveling the state. In the 1990s, government representatives from Malaysia and Venezuela visited the CCBC to learn how to create a state-sponsored center back home.

“It doesn’t seem possible for anyone to replicate it,” says Horning, who has been on the staff since 1982. “They can replicate a part of it but not all of it. And that’s probably because when this library was started — in terms of the economy, in terms of partnerships — it was exactly the right time.”

And it perfectly positioned the CCBC to expose a serious problem in the world of children’s literature.

Diversity in Children’s Books 2018

Percentage of books depicting characters from diverse backgrounds based on the 2018 publishing statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center.

1% American Indians/First Nations

5% Latino/Latina

7% Asian Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific American

10% African/African American

27% Animals/Other

50% White

The All-White World

Ginny Moore Kruse MA’76 was honored, and then alarmed.

In 1985, the American Library Association asked the longtime director of the Cooperative Children’s Book Center to join the national Coretta Scott King Book Award committee. The annual award recognizes outstanding books by black authors and illustrators.

The committee didn’t convene for long. There were only 18 books for consideration — 0.7 percent of the 2,500 published that year.

“I was flabbergasted,” says Kruse, who headed the CCBC from 1976 to 2002.

The same year, Horning received a call from a librarian at a Milwaukee public school looking for multicultural books. “I looked up ‘blacks, fiction’ in the Subject Guide to Children’s Books in Print and found a really small column of books,” Horning says. “Before it, there were a couple of pages labeled ‘bears, fiction.’ It struck me as quite ironic that there were all these books about bears and so few books about black people.”

Horning and Kruse decided to publish the 18-book statistic in the 1985 Choices and vowed to continue tracking diversity among new titles. Their efforts captured the attention of the children’s book world, but underrepresented readers had been aware of the problem for decades.

“We weren’t the first people to realize the paucity of books by African American writers and artists,” Kruse says. “Black librarians, black teachers, black literature experts, black families — they had experienced the lack of books reflecting themselves and their lives. What made the CCBC stats memorable was the numbers confirming the experiences.”

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, portrayals of people of color in children’s books relied on racial stereotypes and caricatures, as in Little Black Sambo. “No matter that my mother said that I was as good as anyone,” children’s author Walter Dean Myers wrote in 1986. “She had also told me, in words and in her obvious pride in my reading, that books were important, and yet it was in books that I found … blacks who were lazy, dirty, and above all, comical.”

Between the 1930s and 1950s, several authors of color found success writing children’s books, including Ann Petry, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, and Yoshiko Uchida. But they were rare and their books exceptions.

In 1965, the Saturday Review rocked the publishing industry with its article “The All-White World of Children’s Books.” Author Nancy Larrick reviewed 5,000 recent books and found that less than 1 percent portrayed contemporary African American life. A librarian told Larrick: “Publishers have participated in a cultural lobotomy,” treating the African American as “a rootless person.”

Around the same time, advocates formed the Council on Interracial Books for Children to encourage authors of color to create books and to push publishers to accept them. In step with the civil rights movement in the late ’60s and early ’70s, multicultural literature proliferated, and literary giants of color emerged — Myers, Virginia Hamilton, Sharon Bell Mathis, Mildred D. Taylor, Lucille Clifton.

And then, for some four decades, progress halted. An economic downturn in the mid-’70s slashed book budgets for public schools and libraries, and “books by minority authors, bought in addition to usual purchases, were the first to go,” USA Today reported in 1989, becoming the first national outlet to cite the CCBC’s data.

With publishers increasingly relying on large bookstores for sales, the long-held notion that black books don’t sell became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Systemic barriers and the editorial instincts of overwhelmingly white publishing houses deterred would-be authors of color.

According to the CCBC’s data, between 1985 and 2014, children’s books by African American authors or illustrators never surpassed 3.5 percent of annual publications. Books containing African American content never reached 6 percent. Even more sparse were books about Asian Americans, Latinos/Latinas, or indigenous people.

Every few years, according to Horning, a new media outlet would pick up the CCBC’s statistics, but the resulting conversation would soon trail off. Then something changed.

#WeNeedDiverseBooks

In 2013, 94 of the 3,200 new children’s books received by the CCBC — 2.9 percent — featured black characters.

Frustrated by the familiar tale, Walter Dean Myers and his son Christopher, also a children’s book author, penned a pair of powerful columns in the New York Times. The younger Myers referred to “the apartheid of literature — in which characters of color are limited to the townships of occasional historical books that concern themselves with the legacies of civil rights and slavery but are never given a pass card to traverse the lands of adventure, curiosity, imagination, or personal growth.”

Later that year, the announcement of an all-white, all-male panel for a major book festival sparked outrage on Twitter. The resulting hashtag, #WeNeedDiverseBooks, evolved into a nonprofit organization that continues to promote diversity in children’s literature and fund programs for aspiring book creators and publishers of color.

The numbers are trending up. Between 2014 and 2018, the CCBC saw books about African Americans and indigenous people roughly double, and books about Asian Americans and Latinos/Latinas triple. The librarians credit scholars and advocates on social media who are keeping the conversation going, as well as independent publishers, such as Lee & Low Books, that are dedicated to diversifying literature.

The progress is still relative. While books about Latinos/Latinas may have tripled, the CCBC has found that they still represent only 6.8 percent of all books. In 2017, a character in a picture book was four times more likely to be a dinosaur than an indigenous child, and two times more likely to be a rabbit than an Asian American child. Only two picture books had a child with a disability as a primary character.

The CCBC now tracks disability and other forms of identity like gender and sexual orientation. Later this year, the center plans to launch a public database logging all of the children’s books it receives. Researchers will be able to easily identify books with specific themes or aspects of representation.

The data have found a permanent home on social media. “We used to see the conversation [on diversity] blow over after a month, but it hasn’t blown over this time,” Horning says. “We get two or three emails and calls a week asking for our stats.”

But with social media comes controversy. And on Twitter, discussion of children’s literature has become contentious, with charges of prejudice and countercharges of censorship.

“Toxic Online Culture”

As a UW senior in 2014, Melanie Kirkwood Marshall camped out in the Cooperative Children’s Book Center to study the representation of black girlhood in young adult literature. The few books she found were disappointingly homogeneous. But now, as a doctoral researcher, she’s noticing promising trends.

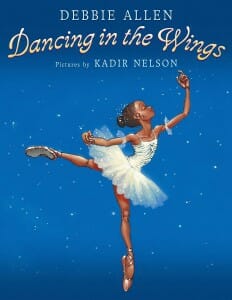

“Not only are we seeing an increase in realistic fiction,” she says, “but there’s an uptick in speculative and science fiction stories. They’re allowing black girls an opportunity to imagine themselves in ways they wouldn’t have before.”

Doctoral researcher Melanie Kirkwood Marshall sees an increase in books “allowing black girls an opportunity to imagine themselves in ways they wouldn’t have before.” LAWRENCE AGYEI

The CCBC librarians note that the #OwnVoices social media movement has paved the way for such stories. It promotes the importance of “cultural insiders” portraying their own identities and experiences.Proponents of #OwnVoices believe that when “cultural outsiders” attempt to write about people from different backgrounds, they’re prone to stumble into problematic representations, ranging from harmful stereotypes to inauthentic narratives. And now, social media critics often condemn books and authors — as renowned as Dr. Seuss and J. K. Rowling — for cultural insensitivities. To some, that’s the price of progress. To others, it’s a slide toward censorship.

The publisher Scholastic famously recalled the 2016 picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington after a social media outcry. Initially praised by reviewers for its tale of the president’s enslaved head chef, the book was denounced for glossing over the horrors of slavery.

Last year, two authors of color pulled their debut young adult novels just prior to publication. A Place for Wolves by Kosoko Jackson, a gay black author, received online criticism for using the Kosovo War as a backdrop for the love story of a non-Muslim American. The fantasy novel Blood Heir by Amélie Wen Zhao, a Chinese immigrant, angered #OwnVoices supporters by allegedly paralleling the history of African American slavery.

“It just snowballed into a lot of people who hadn’t read the book [criticizing it],” Zhao told National Public Radio in November after releasing Blood Heir with revisions.

Some see these anti-book campaigns as an expression of “cancel culture.” Ruth Graham cautioned in Slate: “We’ve gotten an increasingly toxic online culture around [young adult] literature, with ever more baroque standards for who can write about whom under what circumstances. From the outside, this is starting to look like a conversation focused less on literature than obedience.”

By contrast, adherents of #WeNeedDiverseBooks claim they’re protecting children from hurtful material and challenging authors to be more sensitive. They’re happy to wrest some of the power from a publishing industry that’s still 80 percent white and has historically controlled what stories are told. “Social media is giving a voice to a lot of people who never had a platform before,” Horning says.

Equipped for Tomorrow

As the children’s book world grapples with these complex discussions, sociological studies affirm the importance of representation. Research has shown that children notice race as early as six months, begin to internalize bias between the ages of two and five, and can become set in their beliefs by age 12.

“If children grow up never seeing, never reading, never hearing the variety of the wide range of voices, they lose so much,” Kruse told the journal Language Arts in 1993. “They will not be equipped for today, not to mention tomorrow. The world will go right past them. They are going to be stunned when everyone is not like them.”

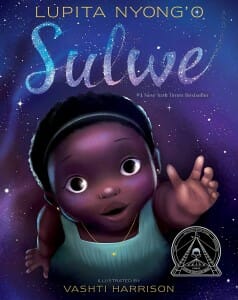

Last year, Kirkwood Marshall became a mother herself. One of the first books she bought her daughter was Sulwe, written by Lupita Nyong’o and illustrated by Vashti Harrison. It follows a young black girl’s journey from being insecure about her skin tone to embracing her unique beauty.

“It’s come full circle,” Kirkwood Marshall says. “I did the same thing [as my mother] — I wrote a note to my daughter in the book. It just says: May you always love your beautiful brown skin.