Concern erupted nationwide last year, after the release of a Centers for Disease Control report indicated that, for the first time in over five decades, Americans were starting to die sooner.

But the document, which made national news, showed a mere 0.1 year decline in average age of death.

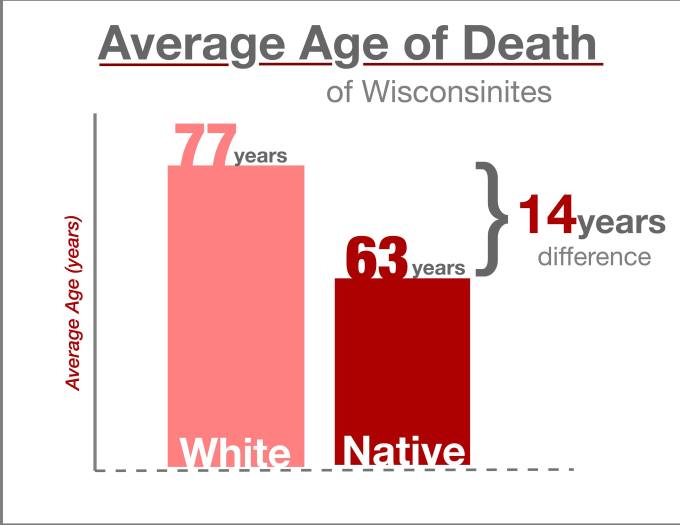

White Wisconsinites currently have an average age at death of 77 years, just below the national norm. But the average Native American will die 14 years sooner, at only 63.

Below-average mortality rates have persisted since European colonization and ethnic cleansing of the region, despite more recent attempts to rectify the problem in the last several decades.

Yet through a series of treaties and federal laws, Native populations are guaranteed free, federally-funded health services — the only demographic in the country with such an assurance.

Most tribes run their own health care systems through the federally-funded Indian Health Services. But it can also be difficult to know where exactly help can be found, because clinics that are not bound to cities or reservations are often few and far between.

Every community is different, just like every person is different. So to assume that we can take a “one size fits all” approach is pretty ignorant, but that’s what we do. We have to be better at assessing community needs with appropriate community input and then design interventions based on that. We have to be smarter to achieve equity.

Tribal communities can also cover vast distances, with Ho-Chunk citizens spread as far north as Green Bay, as far east as Eau Claire and as far south as Madison, since they are not bound to a reservation.

How then, when exorbitant costs dominate the mainstream conversation on health care accessibility, does such inequality still exist?

Part of the problem is a familiar conversation in Wisconsin politics: the rural health care dilemma.

“We’re spread out, with very limited staff to take care of individuals,” said Jess Thill, community health director for the Ho-Chunk Nation. “All rural communities face the challenge of employing qualified staff to keep people healthy for as long as we can.”

And even when facilities do exist in a community, there is no guarantee that they have the resources necessary to support the health needs of tribes.

“In many ways there’s a lot of irony built into the guarantee of health services, because our systems are terribly underfunded.” said Dr. Donald Warne, the chair of the Department of Public Health at North Dakota State University. “We don’t have the resources to address health needs.”

IHS facilities can be extremely beneficial, but they are not always well-equipped or well-funded enough to deal with comprehensive care of all kind, according to Kimberly Mueller, a health care navigator for Covering Wisconsin — a UW Extension project that provides health insurance education and resources.

“It’s about educating Native families about what’s available to them,” Mueller said. “Most times, [IHS facilities] are just small health centers that meet your everyday needs, but when you have specific needs, you may need to go outside of the IHS.”

But being outside of the IHS network also means being outside its free care system. When medical conditions demand expensive surgeries or prolonged treatment, leaving the network can become a financial impossibility to those without additional insurance.

Though rural accessibility and inadequate funding remain pervasive issues, experts say some of the primary causes of these health disparities stretch back centuries.

According to Warne, the answer is not just biological, but historical as well.

“We have seen terrible events occur to American Indian people. Horrible events, attempts at complete genocide that were almost successful,” Warne said during a lecture at UW-Madison. “When we think about that, what’s the impact of that on a population?”

Epigenetics, a new but exploding field, seeks to understand how environmental and social factors impact the ways in which individuals develop biologically.

Research has found that the ways in which organisms interact with their surroundings, the type of society they live within, the types of relationships they have, even the types of affection they receive, can have a profound impact on their general health.

Not only do social and environmental factors impact individual health, but a groundbreaking study found that the nutrition and stress levels of a single person can deeply influence the health outcomes of their descendents.

All rural communities face the challenge of employing qualified staff to keep people healthy for as long as we can.

If significant levels of stress, anxiety and malnutrition may have far-reaching generational consequences, public health experts now wonder how centuries of systematic ethnic cleansing could have impacted health outcomes for Native communities today.

“We haven’t identified the exact mechanisms for how this happens, but I do think that epigenetics will provide a scientific platform through which to better understand the impact of historical trauma,” Warne said. “Populations that have been decimated tend to have far worse health outcomes in subsequent generations, but how to quantify that we haven’t quite figured out yet.”

When the problem is historical, the answer can seem elusive: How does society combat an inequality rooted in injustices of the past?

The best way to address history, Warne argues, lies in planning for the future and a greater emphasis on preventative strategies.

“Working upstream means planning for the next generation, so prevention programs need to include good nutrition and parenting education for people about to have children,” Warne said. “For the people that are here now, we need to have programs that address social determinants of health.”

Social factors like poverty, educational access, and economic opportunity are deeply connected to overall health, according to a study published in Health Affairs, and the poverty rate for Native Americans is almost double the national average.

The difficulty with addressing multifaceted issues is that they demand multifaceted solutions, which tend to be far more difficult to sell politically and enact practically.

“Highly stressful environments and other social determinants, like living in poverty or being homeless, creates worse health outcomes,” Warne stated. “They’re not separate arenas; we tend to look at those issues, whether genetic or social, in their silos, but they interact with each other.”

In order to address the unique needs of populations facing differing social, environmental and genetic challenges to health equity, many are advocating for a more holistic approach to health care: community health.

“When you look at people as individuals with individual illnesses, I don’t think you’re looking at the overall picture of what’s actually causing the illness. That’s what community and public health are all about,” Thill explained.

Community health departments, like the one Thill directs, analyze and address individual health issues within their wider social and environmental context. This wider perspective allows healthcare workers to develop more precise strategies to meet the unique needs of the communities they serve.

Thill’s division provides a series of broad community services to members of the Ho-Chunk nation, such as home visits, personal care, food distribution, nutrition education and resources, and pregnancy services.

Warne argues that getting away from an inflexible approach is necessary to close health disparities between Native and non-Native peoples.

“Every community is different, just like every person is different. So to assume that we can take a ‘one size fits all’ approach is pretty ignorant, but that’s what we do,” Warne said. “We have to be better at assessing community needs with appropriate community input and then design interventions based on that. We have to be smarter to achieve equity.”

Written by Andy Goldstein, The Daily Cardinal