By Kynala Phillips

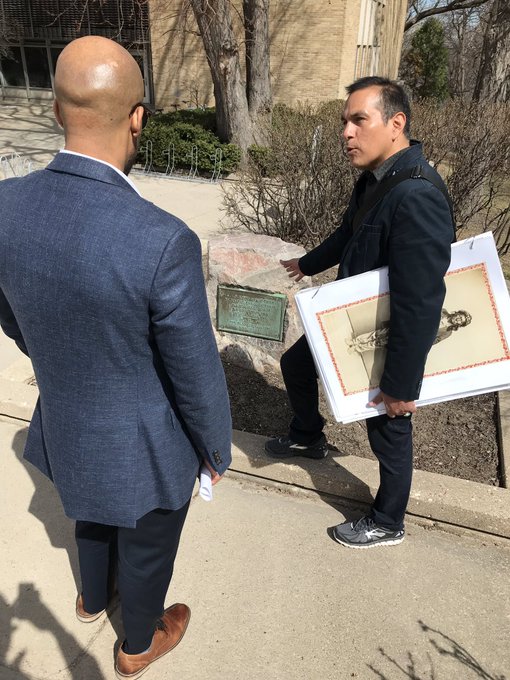

On Tuesday, April 9, Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes took a Native American Cultural Landscapes tour on UW-Madison’s Campus with Assistant Dean Aaron Bird Bear just hours before the State of the Tribes address was delivered at the State Capitol.

“[It’s] likely the most archeology rich campus in the United States,” said Bird Bear. “Incredible layers of humanity in this space,” Bird Bear said as he walked Lt. Gov. Barnes and his staff through Dejope Residence Hall, which was designed in collaboration with UW-Housing and the Ho-Chunk Nation.

The residence hall actively serves as an acknowledgement of the First Nation’s in Wisconsin, especially the Ho-Chunk Nation. Throughout the tour Bird Bear pointed to many significant design elements that pay homage to the people of the First Nations and to educate students on the 12,000 years of humanity that occupied the space. The building itself is also built as a bird as a nod to the many bird-shaped mounds and ancient mounds of earth that shape and contour Wisconsin’s flagship university’s landscape.

According to UW-Madison’s Lakeshore Preserve, many of the earthworks found throughout Madison and the Midwest are called effigy mounds because they are built into to shapes of animals such as bears, turtles, panthers, deer and buffalo.

“The bentley goose is the signature effigy mound of the four lakes,” Bird Bear said, adding that each effigy mound is a burial site. Representational sites like the bentley goose earthworks typically have one person buried underneath, he said.

The remnants of the strong cultural traditions of the Ho-Chunk and other First Nations are a prominent feature of the state. Today there are roughly 38 mounds spanning UW-Madison’s campus, which includes a number of mounds no longer visible. There is an estimated 1,300 extant effigy mounds, constructed between 350 and 2,800 years ago, throughout the city of Madison, according to an article published by UW-Madison Communications.

Yet, despite having the highest concentration of effigy and burial mounds, Madison lost a significant number of these prehistoric landmarks due to agriculture and city development in the 19th century, according to the city of Madison.

“[I] wanted to take this opportunity to learn more about the First Nation’s of Wisconsin and the 11 federally recognized tribes [and] wanted to establish better working relationships knowing that we’re partners in moving the state forward,” said Barnes, who has said his main priorities in office are “Sustainability and Equity.”

Barnes added that “being very attentive and actually listening,” are two ways in which his office intends to mend relationships between Native American tribes and the state. “There was a huge disconnect with the previous administration and you don’t get anywhere if you don’t have conversations with people.”

Bird Bear shared with Barnes the struggles endured to preserve these key landmarks in the state of Wisconsin, specifically efforts to protest a 2016 Assembly bill that threatened the endangered ancestral mounds left in the area. Unique sites visited on the tour also included the nationally recognized double tailed water spirit effigy of the observatory mound group, which is the only one of its kind and is currently being eroded by a sidewalk that violates protection laws that are in place to preserve these landmarks, according to Bird Bear.

“For so long our state has ignored as a people First Nations of the state, particular issues that impact them disproportionately whether it’s mining issues or other environmental issues and we learned more about that today,” Barnes said. “It sort of trends with the historical context of how this state, this nation has treated tribal nations. We got to do a lot better.”

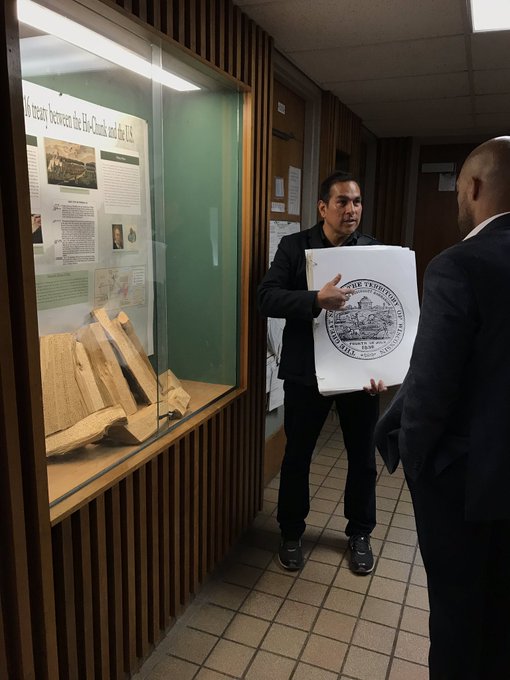

Throughout the tour, Bird Bear offered an extensive overview of the many challenges that the Ho-Chunk Nation and other First Nations faced since the arrival of early European settlers. He also points to the historic Territorial Seal of Wisconsin, created in 1838, which bears the latin phrase “Civilitas Successitt Barbarum” which translates as “civilization succeeds barbarism,” according to Bird Bear.

“When you start in white supremacy, it’s hard to untangle,” Bird Bear said regarding ethnic cleansing in Wisconsin and across the country. “This is the idea of white supremacy, white space and forced removal.”

Barnes’ tour concluded at the top of Bascom Hill where Bird Bear explained to Barnes and his staff the complexities of the two major symbols that overlook UW-Madison campus: A three-panel banner of Bucky Badger that hangs from the columns of Bascom Hall and the infamous statue of Abraham Lincoln.

For historical context, the badger is representative of early settlers in the 1800s who arrived in Wisconsin as lead minors and spent most of their time in mine shafts that reminded many of the badger animal, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society. The incoming flow of settlers combined with the practice of mining directly impacted many First Nations and their livelihood.

President Abraham Lincoln is responsible for ordering the largest public mass execution in U.S. history, murdering 38 Santee Sioux in Minnesota.

“Both of them are a symbol of ethnic cleaning and removal,” Bird Bear said.

“I would encourage people to take this tour, to take time to take the same tour I went on and learn more about the history of the state and learn more about how we have traditionally interacted with Native Americans in Wisconsin,” Barnes said.