One of the first people to apply computers in medicine was a University of Wisconsin computer engineering alumna who was born nearly a century ago in 1924.

Thelma Estrin was an early pioneer of the field of medical informatics — the now commonplace practice of applying computers to medical research and treatment. She also was something of a trailblazer for women hoping to pursue careers in the sciences.

Growing up in New York City, Thelma Austern (who took her husband Jerry’s last name, Estrin, when they married in 1941) always had an aptitude for math and science, but those fields were generally off-limits for women in the years following the Great Depression.

Thelma Estrin was an early pioneer of the field of medical informatics — the now commonplace practice of applying computers to medical research and treatment. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

“I was the first woman engineer I ever knew,” she said in 1982, when receiving an achievement award from the Society of Women Engineers.

That was among her many firsts. In 1961, Estrin published one of the first descriptions of a system to digitize electrical impulses from the nervous system. She went on to author dozens of research papers about mapping the brain with computers during a professional career that spanned some 40 years.

Throughout her career, and especially during the later years, Estrin was a tireless advocate for women in engineering. She knew firsthand how difficult it could be for women to get their feet in the door.

“At school, nobody took me very seriously,” she said in a 1981 interview with the magazine U.S. Woman Engineer. “But I took myself seriously.”

Estrin always knew that women could become exceptional engineers, matching men in technical skill and sometimes surpassing their male colleagues in essential leadership qualities like empathy and communication.

Later in her career, she published multiple papers that set forth strategies for attracting and retaining women in the sciences and organized a series of workshops to help women rise to leadership roles.

Estrin attributed her self-confidence to the influence of her mother, who owned and operated an auto parts store until her marriage to Estrin’s father at the age of 27. Throughout Estrin’s childhood, her mother also was a community leader in their local Democratic party.

And Estrin credited her mother with teaching her that women shouldn’t take a back seat. That lesson persisted, even though her mother died of cancer when Estrin was just 17.

Shortly after Thelma and Jerry married, the United States entered World War II, and everything changed. Factory floors emptied as men deployed overseas and women entered the workforce like never before. It was a blessing in disguise and an opportunity to put her talents to use.

Estrin was a tireless advocate for women in engineering. She knew firsthand how difficult it could be for women to get their feet in the door.

Jerry enlisted in the Army Signal Corps, while Thelma took a three-month short course at Stevens Institute of Technology to become an engineer’s assistant. She began working at the Radio Receptor Company in New York City, where her knack for engineering became apparent; records from that time note: “We have seen Thelma manipulating lathes, shapers and surface grinders and squinting at micrometers and surface gauges with all the aplomb of an experienced toolmaker.”

Toward the end of the war, the Estrins moved to San Bernardino, California, where Thelma worked as a radio technician. After Jerry was discharged, the couple moved to the Midwest, and both enrolled at the University of Wisconsin.

The couple selected the university because a dear friend also was pursuing his degree in Wisconsin.

Supported by teaching stipends, benefits from Jerry’s G.I. Bill, and the sale of Thelma’s mother’s diamond ring, the two both completed their undergraduate and graduate degrees at Wisconsin. Estrin earned her bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering in 1948, 1949 and 1951.

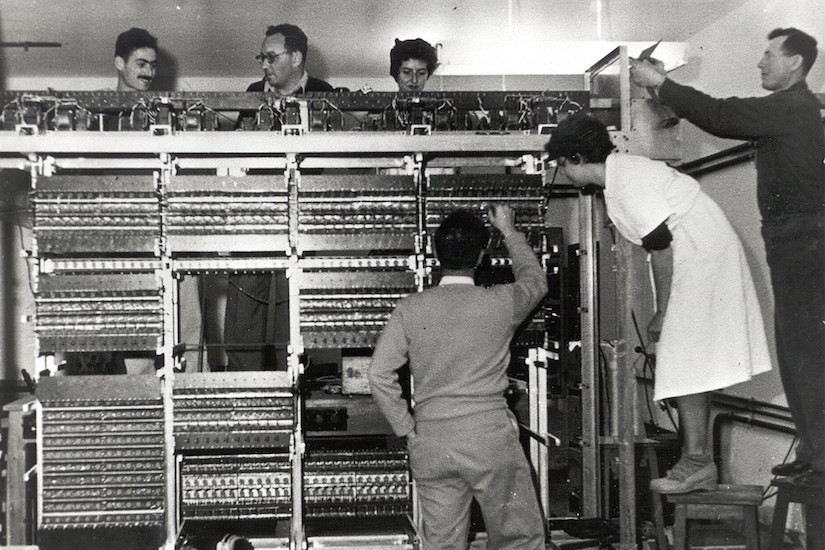

Thelma Estrin working on Israel’s first supercomputer, WEIZAC, in the 1950s. PHOTO: WEIZMANN INSTITUTE

Although Estrin often encountered anti-Semitism and sexism from her classmates, she found a supportive mentor on campus in Professor T.J. Higgins, whose encouragement and openness spurred Estrin on. The two remained confidantes for many years.

For the next four decades, Estrin blazed a trail across the country and around the world in computer science and engineering. She and Jerry built Israel’s first supercomputer, a hulking behemoth named WEIZIAC. After joining the faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles, working in its then-nascent Brain Research Institute, Estrin was lead engineer on the country’s first grant for establishing a computer facility at a medical school.

Estrin became director of the Brain Research Institute’s nationally renowned data processing laboratory in 1970 and later developed a computer network between UCLA and the University of California, Davis. As her career progressed, she became interested in how computers could help clinicians make better decisions and contributed to developing EMERGE, a first-of-its-kind system to guide emergency room personnel in treating chest pain.

Estrin was the first woman elected to the board of IEEE — the world’s largest technical professional organization for technology advancement. COURTESY OF IEEE HISTORY CENTER © IEEE

Active in several scientific societies, Estrin was the first woman elected to the board of IEEE — the world’s largest technical professional organization for technology advancement — as well as its first female vice president. Additionally, as a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Estrin led the engineering and computer sections in 1989 and 1994, respectively.

She retired in 1991 and died in 2014.

Even though Estrin was the first woman engineer that she herself ever knew, her skill and tenacity helped countless other women follow in her footsteps.

“Refusing to be daunted by prejudice, she demonstrated through the undeniable quality of her work that talent is not tied to gender,” read the citation for Estrin’s honorary doctor of science degree from UW–Madison, which was awarded in 1989. “She has been a model for other women who have entered and enriched the field of engineering.”

This story is part of the UW Women at 150 series marking the 150th anniversary of the first women receiving undergraduate degrees at the university. Over the course of this academic year, University Communications will feature stories that celebrate the accomplishments of women at UW–Madison through the decades and recognize the challenges that remain, as well as the ways our views of gender have evolved and expanded.