While many people know “A Raisin in the Sun,” having seen the play or movie, far fewer know much about its author, Lorraine Hansberry. Although Hansberry spent less than two years as a student at UW–Madison, it was an important part of her journey as a writer and activist.

Imani Perry, a professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, wants more people to know about the author, the activist and the woman.

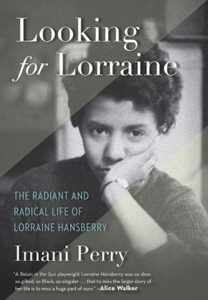

“Hers is a story that remains in the gaps despite the fact that she was widely influential. Her image in the public arena has a persistent flatness, even now as more people know about the details of her life. Knowing only two dimensions is our misfortune. She sparked and sparkled,” Perry writes in her new book “Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry.”

Hansberry’s parents were college educated. Her father was a successful Chicago real estate entrepreneur. Her parents often hosted some of the most progressive black intellectuals in the country, including W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. They encouraged her to pursue education.

When it came time to select a college, Perry writes, “Lorraine chose to step into uncharted territory: the large, progressive, and populist University of Wisconsin at Madison, where only a smattering of black students had enrolled since 1875. Her first major life decision, though a temporary one, would set her on an unexpected and extraordinary course.”

“A woman who is willing to be herself and pursue her own potential runs not so much the risk of loneliness, as the challenge of exposure to more interesting men — and people in general.” — Lorraine Hansberry

It was 1948. Some black students lived off campus; housing discrimination was common. Lorraine’s mother wanted her to live in a residence hall. Langdon Manor, a housing group for female artists and writers, was suggested.

“Langdon Manor was already diverse, including Jewish and Hawaiian students in their number,” Perry writes. “But a black girl, of course, was a different matter entirely.”

“The entire group was won over by her warmth and charm at that first meeting,” said JoAnn Beier. “She spread her own brand of fairy godmother’s dust upon us, which fell like the first light snow of a winter’s evening, the kind you want to keep and save.”Before she could move in, Hansberry had to come to dinner with the current residents, who would then vote on whether she could live with them.

The vote was unanimous in her favor. “The women also felt rather self-congratulatory about welcoming the ‘first’ of her kind,” Perry writes.

Hansberry majored in art, taking classes in stage design and sculpture. She developed a deep appreciation for truth in art and was particularly influenced by a performance of “Juno and the Paycock” by Irish playwright Sean O’Casey.

“He wasn’t concerned with making sure the Irish looked good or countered stereotypes,” Perry writes. “He freed her from a sense that as a black writer one had to constantly be worried about depicting characters who were ‘credits to their race,’ as the commonplace saying went.”

“Don’t get up. Just sit a while and think. Never be afraid to sit a while and think.” — Lorraine Hansberry

As a high school student, Hansberry had served as president of the Forum, a student organization that focused on international issues, says Sandra Adell, a professor of Afro-American Studies at UW–Madison. “She therefore came to Madison with rather sophisticated ideas about progressive social and political movements, considering her age, and quickly became involved with the UW–Madison campus branch of the Young Progressives of America, and served as its president.”

Her political interests expanded. She worked on the presidential campaign of Henry Wallace, the nominee of the revived Progressive Party.

“Being in a predominately white university, while in some ways isolating, also somewhat surprisingly provided a space for her to find and exercise a political voice beyond the circumscribed set of issues, that is advocacy of civil rights within its most common frame of that period — and anticommunist liberalism — to which women of her race and class were often resigned,” Perry writes.

Classmate Bob Teague, a Badger football player who went on to become one of the first black TV journalists in New York, remembered her as “the only girl I knew who could whip together a fresh picket sign with her own hands, at a moment’s notice, for any cause or occasion.”

Lorraine Hansberry was learning a lot. But she struggled academically and was placed on probation.

She continued to encounter racism throughout her two years on campus. She and housemate JoAnn Beier made plans to get an apartment of their own, but Beier’s parents wouldn’t allow it. Beier didn’t have the courage to tell her friend. She asked the house mother to do it for her.

“JoAnn wrote that afterwards their friendship was never the same,” Adell says. Hansberry left at the end of that semester.

“It’s uncertain whether racism is what caused her to leave and not continue pursuing an undergraduate degree,” Adell says. “She was, by her own admission, not a good student, perhaps because she was already a young intellectual of the political left and needed to be in an environment that was much more stimulating than a university campus.”

“There is always something left to love. And if you ain’t learned that, you ain’t learned nothing.” — Lorraine Hansberry

Hansberry set out to be a writer in New York and worked for Paul Robeson’s newspaper, Freedom. She covered both national and international stories.

“She was a lifelong activist and believed that artists and writers had a responsibility to use their talents in the struggle against racism and oppression, not just in the U.S., but globally,” Adell says.

She also began writing a play. It was the story of the Youngers, a multi-generational African-American family who shared a cramped Chicago tenement during the time of segregation. It was greatly influenced by her own upbringing.

Success wasn’t immediate. All but one of the characters were black. It took over a year for the producer to raise enough money to launch it.

But then the curtain opened on Broadway at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on March 11, 1959.

Audiences were enthralled.

“This play resonated with black people because it was the first time that we saw representations of ourselves on this country’s main stages as hardworking people trying to achieve some version of the American Dream, rather than as maids, butlers, and other roles that did nothing more than disseminate negative images and stereotypes of African Americans,” Adell says.

The play, starring Sidney Poitier and Ruby Dee, closed on Broadway June 25, 1960, after 530 performances. Hansberry was the first black woman to have a play produced on Broadway and the youngest playwright to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award.

In 1961, it was made into a film. It’s seen two Broadway revivals, one starring Denzel Washington. Although written more than 60 years ago, the story continues to find an audience.

“It continues to resonate because, as Hansberry once wrote to her mother, it shows black people as human, with dignity, pride, and flaws. It’s a play about a black family living on the South Side of Chicago. That’s what Hansberry in an interview referred to as the ‘particular,’” Adell says. “The play is race-specific. But it also is universal, in that it explores, within its particularity, universal ideals: love, desire, dreams, anger, humor, and sometimes, hate, although there’s not much hatred in this play.”

“I care. I care about it all. It takes too much energy not to care.” — Lorraine Hansberry

Emily Auerbach, a UW–Madison professor of English, teaches “A Raisin in the Sun” every year to students in the Odyssey Project, which offers humanities classes to adult students facing economic barriers to college.

“Whether students are from Chicago, like Hansberry, or from Mexico, Tibet or Togo, they all can relate to the family members in the play and their struggles against an oppressive society,” Auerbach says.

And it gives hope.

“Hansberry teaches her readers empathy, tolerance, love, family loyalty, dignity, and a hatred of injustice,” Auerbach says.

Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer in 1965, at the age of 34. Long after her death, her talents are still being recognized. In 2010, she was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame and in 2013, into the American Theater Hall of Fame. In January, the PBS series “American Masters” released a new documentary, “Lorraine Hansberry: Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart,” directed by Tracy Heather Strain. And she is among the more than 50 people featured in the Wisconsin Alumni Association’s Alumni Park.

“Measured by any standard, Hansberry ranks in the very top tier of American dramatists, alongside Eugene O’Neill and Tony Kushner,” says Craig Werner, a professor of Afro-American Studies. “‘A Raisin in the Sun’ combines realistic power and lyrical brilliance. It’s deeply grounded in its moment, but touches on human and political realities that resonate as deeply today as they did when it debuted.”

Hansberry defied stereotypes.

She was a black lesbian born into the middle class who became a Greenwich Village bohemian leftist married to a man, a Jewish communist songwriter, Perry writes.

“Though it be a thrilling and marvelous thing to be merely young and gifted in such times, it is doubly so — doubly dynamic — to be young, gifted and black.” — Lorraine Hansberry

There is so much more to be said about her. Fortunately, Perry’s book has sparked renewed interest in both Hansberry’s life and her work.

“Lorraine Hansberry displayed tremendous courage in her lifetime, turning the racism of her era into groundbreaking plays that challenged America’s notions of humanity,” Auerbach says.

Although she didn’t earn a college degree, much can be learned from that, Perry said in an interview with the Chicago Tribune.

“I think it is important to tell young people that academic success is wonderful, but it’s not the only way to cultivate your mind or to become excellent and those types of models,” Perry said. “We need to have them and to acknowledge them in that way, because we have kids who think that they are stupid because they struggle in school. There are these models, geniuses, for whom that institution didn’t necessarily work, but that didn’t get in their way of their intellectual development.”

While it’s easy to wonder what more Hansberry could have achieved had she lived longer, Perry focuses on what Lorraine was able to accomplish and how she continues to inspire.

“The urgency with which she lived, especially in her final days when she was literally running out of time, was infused with the sense of the possible,” Perry writes. “Peace, justice, love, beauty — she believed they could all be achieved, and that we ought to reach for them.”

This story is part of the UW Women at 150 series marking the 150th anniversary of the first women receiving undergraduate degrees at the university. Over the course of this academic year, University Communications will feature stories that celebrate the accomplishments of women at UW–Madison through the decades and recognize the challenges that remain, as well as the ways our views of gender have evolved and expanded.