November is National American Indian Heritage Month The Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum join in paying tribute to the rich ancestry and traditions of Native Americans.

What started at the turn of the century as an effort to gain a day of recognition for the significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S., has resulted in a whole month being designated for that purpose.

One of the very proponents of an American Indian Day was Dr. Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca Indian, who was the director of the Museum of Arts and Science in Rochester, N.Y. He persuaded the Boy Scouts of America to set aside a day for the “First Americans” and for three years they adopted such a day. In 1915, the annual Congress of the American Indian Association meeting in Lawrence, Kans., formally approved a plan concerning American Indian Day. It directed its president, Rev. Sherman Coolidge, an Arapahoe, to call upon the country to observe such a day. Coolidge issued a proclamation on Sept. 28, 1915, which declared the second Saturday of each May as an American Indian Day and contained the first formal appeal for recognition of Indians as citizens.

The year before this proclamation was issued, Red Fox James, a Blackfoot Indian, rode horseback from state to state seeking approval for a day to honor Indians. On December 14, 1915, he presented the endorsements of 24 state governments at the White House. There is no record, however, of such a national day being proclaimed.The first American Indian Day in a state was declared on the second Saturday in May 1916 by the governor of New York. Several states celebrate the fourth Friday in September. In Illinois, for example, legislators enacted such a day in 1919. Presently, several states have designated Columbus Day as Native American Day, but it continues to be a day we observe without any recognition as a national legal holiday.In 1990 President George H. W. Bush approved a joint resolution designating November 1990 “National American Indian Heritage Month.” Similar proclamations, under variants on the name (including “Native American Heritage Month” and “National American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month”) have been issued each year since 1994.

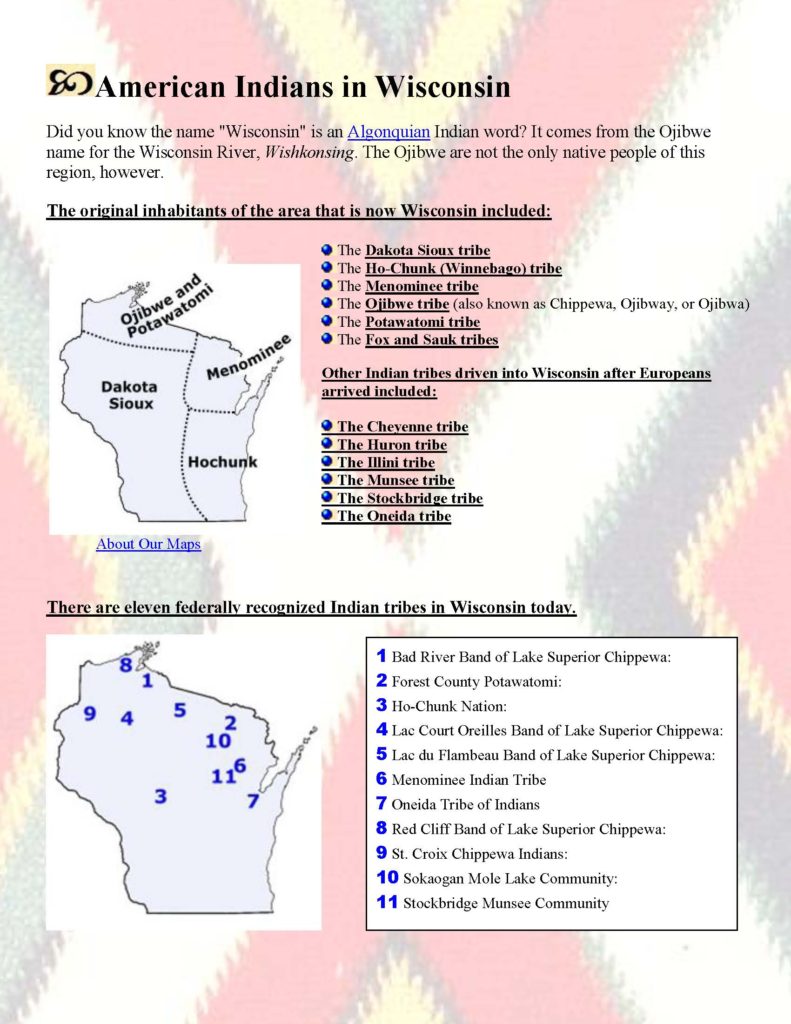

American Indians in Wisconsin – History

The American Indian population in Wisconsin dates back centuries. Their presence in this state predates Wisconsin statehood and the majority of the population who came during that time. Evidence suggests that the early peoples of Wisconsin arrived about 10,000 years ago.1 Archeologists have found many clues of the past lives of the Native peoples in this region through excavation of sites all across the state. Effigy mounds, mounds in the shape of animals, have been found as burial sites for the early Wisconsin inhabitants.2 Mississippian culture was also a significant era in the history of the early populations in Wisconsin over 1,000 years ago.

In Wisconsin, these people are called Oneota.3 They lived in villages and planted gardens to grow crops such as corn, beans and squash.4 They had a complex trade network that extended to both the Atlantic and the Gulf coasts.5 Before European contact, American Indians lived throughout the area where Wisconsin is today. They lived off the land, farming, hunting and gathering, maintaining strong family ties and cultural traditions within their respective tribes. American Indians in Wisconsin have a rich cultural heritage that is been passed down from generation to generation by tribal elders. The presence of European settlers drastically altered their way of life.

The American Indian population in Wisconsin first saw White settlers with the arrival of French and English fur traders. The first were French trader Jean Nicolet and the missionary Jacques Marquette near the Red Banks in 1634..6 During this time, fur was the main focus and fur traders and missionaries worked with the American Indians to achieve their objectives for over 150 years.7 However, this changed when settlers came to Wisconsin. The American government was established and the population continued to increase. America began to expand west to make room for the incoming settlers, without regard to the lives of American Indians.

In 1804, the government forced the Sauk and Fox tribes to cede their land claims in southern Wisconsin in a treaty they had not agreed to..8 These actions led to the Black Hawk War of 1832. The largest American Indian population in Wisconsin, the Menominee, was pressured to sell away 11,600 square miles of land along the lower Fox River.9 The Treaty of Prairie du Chien of 1825 was significant in the history of American Indians in Wisconsin, after European settlement. The treaty was facilitated by the United States government to end the inter-tribal warfare that was disrupting the fur trade and creating tensions between settlers and the tribes.10 The tension between tribes was created because the United States government had used them against each other to gain more lands.11 The Treaty of Prairie du Chien established a treaty of peace among the tribes and demarcated boundaries between settlers and American Indians.

The Bad River Lapointe Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians are a federally recognized tribe of Ojibwe people. The Bad River Reservation is located on the south shore of Lake Superior and has a land area of 156,000 acres (244 sq mi; 630 km2) in northern Wisconsin straddling Ashland and Iron counties. The tribe has approximately 7,000 members, of whom about 1,800 lived on the reservation during the 2000 census.[1]![The Bad River Lapointe Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians are a federally recognized tribe of Ojibwe people. The Bad River Reservation is located on the south shore of Lake Superior and has a land area of 156,000 acres (244 sq mi; 630 km2) in northern Wisconsin straddling Ashland and Iron counties. The tribe has approximately 7,000 members, of whom about 1,800 lived on the reservation during the 2000 census.[1]](https://diversity.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Chippewa_men_Bad_River-300x274.jpg)

By 1971, most American Indians had been placed on reservations and the government discontinued its use of treaties with them.13 The government changed its focus to “de-Indianizing” this population, creating schools that attempted to rid them of their cultural traditions and ways of life by breaking tribal ties and molding them into the image of white settlers.14 However, before this time, between the late nineteenth century through the 1920s, the federal government aimed to mainstream Native Americans through the policies of assimilation and allotment.15 Some of these schools included Menominee Boarding School at Keshena, Oneida Boarding School at Oneida, Lac du Flambeau Boarding School at Lac du Flambeau, and Tomah Industrial School at Tomah.16American Indians represent diverse nations of people who flourished in North America for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. The Menominee, Ojibwe (Chippewa), Potawatomi, and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) peoples are among the original inhabitants of Wisconsin. American Indian people are heterogeneous and their histories differ based on tribal affiliation. These groups have tribal councils, or governments, which provide leadership to the tribe. American Indians continue to maintain a strong presence in Wisconsin, and traditional beliefs and practices remain prominent in American Indian culture. As with all groups, there are differences in social, economic, and geographic conditions in American Indian communities that affect health status and access to care.

The Menominee, Ojibwe (Chippewa), Potawatomi, and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) peoples are among the original inhabitants of Wisconsin. American Indian people are heterogeneous and their histories differ based on tribal affiliation. These groups have tribal councils, or governments, which provide leadership to the tribe. American Indians continue to maintain a strong presence in Wisconsin, and traditional beliefs and practices remain prominent in American Indian culture. As with all groups, there are differences in social, economic, and geographic conditions in American Indian communities that affect health status and access to care.

In their attempt to assimilate the Native populations, Congress passed the General Allotment Act of 1887, or the Dawes Act. The Dawes Act changed the ownership of tribal lands to individual ownership of 80-acre parcels. The extra land was sold to Whites to expose the American Indian population to mainstream society. Many tribes had lost even more of their land. For example, the Ojibwe lost more than 40 percent of their homelands to this Act.17 In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA).18 This reversed the Dawes Act, and encouraged tribes to form tribal governments, draft constitutions, and provided political bodies that could assert their sovereign rights.19

In the 1950s, critics began to gain ground in their opposition to the Indian Reorganization Act and argued to dismantle the reservation system and free the federal government from the cost of protecting American Indians and their property.20 The House Concurrent Resolution 108 (passed in 1953) created goals of “termination and relocation,” which were intended to move these populations from rural reservations to urban areas through job training programs and housing assistance.21 Most Wisconsin Indians who opted for this received one-way bus tickets to Chicago, Milwaukee, or St. Paul.22 This termination policy ended the federal recognition of more than 50 tribal governments, including the Menominee, who were one of the first tribes to undergo termination.23 Termination brought disastrous effects to this tribe, but with the help of a grassroots activist group, Determination of Rights and Unity for Menominee Shareholders (DRUMS), the Menominee were able to restore their status by 1975.24

In 1987, Wisconsin held a referendum that approved the creation of the state lottery and gave Wisconsin tribes the right to establish casino gambling.25 Many tribes created casinos as an opportunity to bring economic benefits to reservation communities, including the Ho-Chunk, Ojibwe, Mohican, and Potawatomi.26

For more than a century, Wisconsin tribes have fought to maintain their sovereignty and self-determination in the face of federal policies of assimilation, allotment, and termination. In the last generation, the tribes’ legal status has been clearly defined, their traditional treaty rights guaranteed, and their economic base boosted by gaming and tourism.27